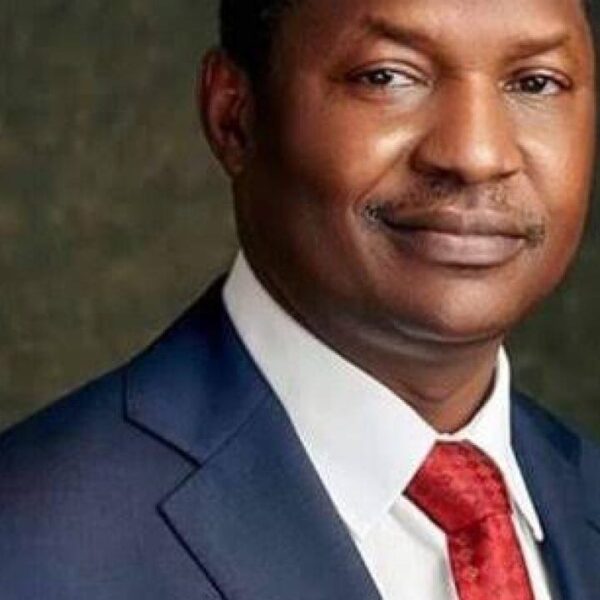

An Associate Professor of International Law, Dr Arinze Abuah, who is the Dean, Faculty of Law, University of Abuja, in this interview with ADE ADESOMOJU, speaks on the impact of conflicting court decisions on the teaching of law

The Faculty of Law, University of Abuja has operated for over three decades; but it only recently secured full accreditation by the National Universities Commission. Why did it take so long?

Four key factors are considered when it comes to issues of accreditation. These are physical infrastructure, staffing, academic content and the students-lecturers population ratio. The state of your library is also key. These go a long way in determining whether the faculty will be accorded interim or full accreditation. In all these critical areas, before the full accreditation, the Faculty of Law, University of Abuja was found to be adequately equipped; the physical infrastructure met the NUC requirements, the academic content was satisfactory and the staffing was excellent.

In the faculty, the university boasts a lot of professors and this is very critical when it comes to the issue of accreditation. The library was also found to be adequately equipped with current journals, textbooks and e-learning facilities. With all these provided, even before the conclusion of the exercise, we knew that the faculty was coasting to a full accreditation status and this was made realisable by the collective efforts of all the members of staff, the faculty management and the students. But I want to thank, especially, my Vice-Chancellor, Prof. Abdul Rasheed Na’Allah, for making this rare feat of full accreditation status a reality. He did not hesitate to deploy necessary and needed resources to make it happen.

Will the NUC accreditation make the Council of Legal Education’s accreditation automatic?

No. The Council of Legal Education’s assessment will be independent of what the NUC panel has done. The Council of Legal Education is coming for its own independent assessment of the faculty. But we don’t expect anything less. In fact, we expect that if there is anything more than full accreditation, we will get it. This is because there are more physical infrastructures coming up and we are hopeful that before their visit, those structures will be ready.

There are two structures going on in the faculty – the lecture theatre with a sitting capacity of 500; and the two departmental buildings with classrooms with 200 sitting capacity each. These will be an advantage to the faculty when the Council of Legal Education panel comes.

Before the NUC full accreditation, you had produced many law graduates, who are now practising lawyers. What difference will the NUC’s full accreditation make for your graduates?

Before now, we were having interim accreditations. The implication of the full accreditation we have just secured is that for the five years coming, the NUC has no business coming to the university to assess whatever we have. But when we were given interim accreditation, it was just for a period of two years after which you are revisited and if the university is found lacking in anything after two years they will deny you accreditation.

Do you agree with those who blame the unethical behaviour of some lawyers on the faculties they graduated from?

I don’t. Lawyers themselves don’t exist in isolation. They are products of society. It is just like a child who decides to veer off the family tradition. Will you blame the family for the child’s misbehaviour? He may have come out of a good family, but got influenced by peer group or the get-rich syndrome. The practice we have today is not as a result of the university background of any lawyer, but as a result of certain peculiar circumstances which we must blame squarely on society.

Why have lawyers lost their influence on society?

Society is dynamic. The pride of every lawyer is the judiciary. When the judiciary loses its spice, it trickles down to the lawyers because they are inseparable. The value attached to lawyers started dwindling the moment aspersions were being cast on the judiciary.

Are these aspersions not justified?

Some of the aspersions are justified, some are not justified. It is unfortunate that the people who are being castigated are not in the position to defend themselves and no law shields them. People, in the name of freedom of speech, say things against defenceless people who are not shielded by law. When we cast aspersions on judges, let whatever we say about them be constructive and substantiated.

Does the spate of conflicting decisions by judges not justify some of these aspersions being cast on them?

Well, it does because where judgments are not consistent, there is no certainty. Where there is no consistency in the judgments delivered, it affects the rules of precedent. Where there are conflicting judgments on an issue, especially judgments of the superior courts, it raises the question: which one forms the precedent? A situation where lawyers are left to pick and choose which of the precedents to follow makes the law uncertain.

Does it, in any way, make the teaching of law difficult for you?

Definitely. The principle is that where you cannot point to anything as stare decisis, you must follow the law; and following the law means you go by precedent. But I am teaching a student to go by this principle of law, and there are two conflicting court decisions on the same principle. It leaves me to pick and choose. I will then start telling the students this is a judgment, this is another judgment on the same issue. This does not augur well. So, what do you tell the students about the rules of precedent? There will be no rules of precedent, if law is not certain on an issue.

How is the academic environment responding to this?

What we do in the academic environment is to drop the two judgments before the students and say pick the flaws in one of them and justify the other.

SOURCE: Punch – https://punchng.com/conflicting-court-decisions-make-law-teaching-difficult-abuah/